Covid-19, obesity, mental health, and the myth of self-control

The Covid-19 pandemic has had a profoundly negative effect on us, yet something useful may come from it. The pandemic has the potential to draw our attention to, and improve our understanding of pathologies that have been ticking away under the surface for decades

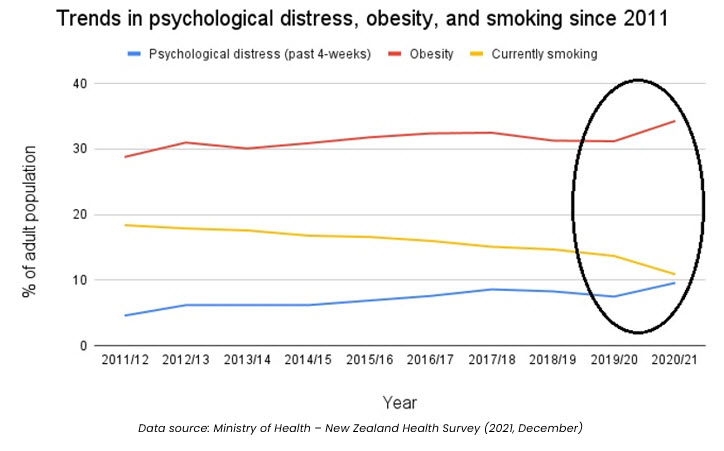

By the numbers

The 2020/21 New Zealand Health Survey [1] revealed some significant changes to several well-established trends, as highlighted below. Before we make sense of these changes, we’ll clarify what was being measured and talk you through the numbers.

Psychological distress

The psychological distress measure captures an adult’s experience of symptoms such as anxiety, psychological fatigue, or depression in the four weeks prior to measurement.

Psychological distress is not to be confused with infrequently feeling unhappy, stressed, or anxious. To be classified as suffering from psychological distress a person must score highly or very highly on a twelve-question distress scale. Where people have such levels of psychological distress it is considered a high probability that they also have an anxiety or depressive disorder.

The measure has captured a steady increase in psychological distress over the past 10 years. However, between the 2019/20 and 2020/21 measurements its prevalence increased from 7.5% to 9.6% of the adult population. This is a jump of 28% over this one-year time-period.

Obesity

The obesity measure captures the proportion of the adult population whose Body Mass Index (BMI) exceeds 30.

Obesity rates have been rising steadily in New Zealand for some time now. However, the prevalence of adult obesity increased sharply from 31.2% in 2019/20 to 34.3% in 2020/21. This equates to a 10% increase over this one-year time-period.

The increase suggests that we increased our food intake during the pandemic which is probably correct. However, the increase coincided with a reduction in the proportion of adults eating the recommended 3+ daily servings of vegetables and 2+ servings of fruit. In 2019/20, 33.3% of the adult population met the recommendation. This dropped to 30.1% in 2020/21, equating to a 9.6% reduction.

We may have increased our food intake, but it certainly wasn’t the types of food we’re encouraged to eat more of.

Smoking

The smoking measure captures people who currently smoke at least monthly and have smoked more than 100 cigarettes over their entire life.

The trend for smoking has shown a steady decrease over the past 10 years. It’s important to note that in 2010 the Government introduced the first of its tax increases designed to raise the price of tobacco products by 10% every year for 10 years. This, alongside other environmental controls such as smokefree areas, helps to explain the steady reduction in smoking.

Between 2019/20 and 2020/21, the number of adult smokers dropped from 13.7% to 10.9%, a sharp reduction of 20.44% that isn’t explained by the annual price hikes.

From a basic statistical perspective, with large population studies such as the annual health survey, we’re looking for changes larger than 5% between years. Such changes suggest that the deviation from the trend cannot simply be attributed to statistical error or the annual variation that we might expect. They suggest that something happened outside of the normal which had a significant effect on psychological distress, obesity, and smoking.

Why is obesity and stress up, and smoking down?

As you’ve probably figured, the major event that occurred over the 2019/20 and 2020/21 period was the Covid-19 pandemic.

COVID seems to have dominated our lives since 2020. The media have made it a priority to report local and international infection, hospitalisation, and death rates on a daily basis. We’ve been through lockdowns where we’ve had to isolate ourselves from social contact. And we’ve had restrictions placed on simple freedoms that we’ve previously taken for granted.

For much of the pandemic there have been two constants – uncertainty and worry.

Uncertainty over when lockdowns will end, when restrictions will end, and when the pandemic itself will end. And worry over the consequences of infections for people, their families, and friends. There’s also constant worry about whether we’ll be able to access treatments and care if needed.

Additionally, many worry about employment and the future in general. Consumer confidence, an economic indicator that measures the degree of optimism consumers have regarding the state of the country’s economy and their own financial situation, is at its lowest level since 2004 when data capture began.[2]

With COVID in mind, the significant increase in psychological distress makes perfect sense. In many regards, it’s surprising that it’s not higher – but we’ll see what the 2021/22 health survey reveals.

It’s important to note that the proportion of adults who met the ‘psychological distress’ criteria in the health survey are in many regards the tip of the ice-berg; they provide insight into bigger problems underneath. A much greater number of people are likely to have suffered or be suffering psychological distress, just not at the frequency and intensity required to meet the measurement criteria used in this health survey.

It’s also worth noting that the trend lines for psychological distress and obesity have been virtually identical over the past 10 years. Not only is our society becoming more obese; it’s becoming more psychologically distressed. Perhaps the two are linked or at least share pathologies.

The good thing is that people seem to be relying less on tobacco to deal with or alleviate their distress. Perhaps the decline in smoking is a positive sign that governments can act to address significant problems and their actions can have a significant impact. So, maybe they should act on other major issues that cause distress such as climate change or housing!

This doesn’t explain the sharp drop in smoking that has occurred during the pandemic though.

Perhaps people stopped smoking when they realised that COVID attacks the respiratory system and as such, smoking increased their vulnerability to the virus. Perhaps people stopped smoking to save money due to concerns about their future employment. After all, smoking rates are higher in populations living in the more socioeconomically deprived areas of New Zealand.

At this early stage though we’re just speculating.

However, the cynic in me thinks that cigarettes were likely substituted for another substance that fulfils the same needs via a slightly different delivery mechanism, and I’m not talking about vaping

“Everything that feels good is either illegal, immoral, or fattening” (Frank Rand)

In the field of addiction, Dr Gabor Maté [3], is one of the worlds most revered clinicians. He observes that addictions always originate from pain; addictive substances are used to help people escape or relieve their pain or distress.

A successful business executive might occasionally use cocaine for the intense rush of pleasure that it provides, without the fear of becoming addicted because their daily reality is likely to be pleasant. However, when a person’s daily reality is anything but pleasant their need to escape is much greater. Hence, their vulnerability to addictive substances is greater because they have a semi-permanent need to escape and seek relief from their current reality.

In recent years scientists have started looking at the addictive nature of modern, high incentive foods (those loaded with extra salt, sugar, and fat) to try and understand why we eat, and why we have a problem with obesity. In the lab, Paul Kenny [4],[5] found that when presented with a choice, rats would prefer to consume a sweet saccharin solution over cocaine. He also found that despite normal food being made available, rats would voluntarily expose themselves to conditions of extreme cold, noxious heat, or electric shocks to obtain food items such as Coca-Cola, M&Ms, shortcake, chocolate chips and meat pate’.

In comparing the responses to drug taking and the overconsumption of high incentive foods, Kenny discovered that both create a feedback loop in the brains reward centres where the more that people consume, they more they crave and the harder it is to satisfy these cravings. These cravings drive an increase in consumption as people try to gain the same reward that they initially attained from a smaller quantity of substance.

At a biological level, this is the neurological response that underpins addiction.

Kenny, and an increasing number of scientists don’t attribute obesity to a lack of willpower. Rather, they argue that obesity is caused by hedonic (pleasure-related) overeating that hijacks the brains reward networks in the same way that addictive drugs do.

I suspect that the sharp drop in smoking over the covid period is best explained via the principle of substitution; at a time of increased psychological distress, people found that high incentive food was quite simply a better provider of pleasure and escape from distress, than tobacco. And, where tobacco products are increasingly hard to access, high incentive foods are everywhere, socially acceptable, heavily promoted, and comparatively cheap.

It's worth remembering that during COVID lockdowns in Auckland the police were pulling over car’s and finding boots full of KFC as Aucklanders resorted to travelling outside their restricted area for their fast-food fix. And when lockdowns ended, TV reporters would film their first segments outside fast-food restaurants, as if restricted access to fast-food was the issue people suffered from most.

As George Bernard Shaw states: ‘there is no sincerer love than the love of food’. For many, ultra-processed junk food and fast-food have become the preferred source of pleasure and means to alleviate psychological distress. This begs an important question – how easy will it be for people to give these foods up when they realise how ‘addictive’ they are and how closely linked they are to obesity and ill-health?

Will people be able to use self-control to resist the abundance of food temptations that surround them?

Unpacking the myth of self-control

Self-control refers to the ability to resist one’s impulses in the service of greater goals or priorities. It is believed by many to be the cure for a variety of today’s problems whether that be the battle with obesity, or a solution to drug addiction and criminal behaviour. Fortunately, these beliefs are coming under increased academic scrutiny.

In 2017, researchers Milyavskaya and Inzlicht [6] followed a group of university students over the course of one semester, monitoring the frequency of, and responses to temptations that might conflict with the students goals.

They found that students reported the experience of using self-control to resist temptations as being ‘cognitively depleting’ (inducing feelings of mental fatigue and tiredness). The study found that students who experienced more temptations were less likely to achieve their goals than those who experienced fewer temptations in the first place.

The implication here is that helping people to remove the temptations that are available to them in their environment is more useful than directing them to use self-control to resist those temptations.

A year later, Milyavskaya and Inzlicht [7] added to this finding by investigating the relationship between self-control, attentional focus and shifting goal priorities.

They found that satisfying immediate goals such as addressing hunger pangs, tends to outweigh longer term goals such as losing weight. And as people’s attention shifts to satisfying such immediate goals, the subjective value they attach to foods and drinks that are immediately available increases.

Regarding obesity, the idea that people can use self-control to resist the abundance of high incentive foods that are easily accessed, socially normalised, manufactured to emphasise hedonic properties, and relentlessly promoted, is frankly ridiculous.

The idea shifts the responsibility for ‘resisting temptation’ onto those who need help to deal with the numerous obstacles the obesogenic environment throws at them. It detracts us from learning about how to help people reduce their exposure to high incentive foods, so they experience fewer temptations in the first place. And it detracts us all from demanding that our leaders follow the advice of public health experts and start putting controls on the availability and promotion of such foods.

The reality of modern-day life, especially during the pandemic, is that for many of us, our cognitive resources, and hence our ability to use ‘self-control’ are already depleted as we deal with; uncertainty and worry on top of regular financial, familial, relationship, and employment stressors. When people are stressed then relieving that immediate stress will always be prioritised over longer-term goals such as losing weight.

What does this mean for how we understand and treat obesity?

COVID-19 has highlighted one thing in particular – as a society, we’re in trouble. The dramatic increases in obesity and psychological distress attest to that. At a population level we need to change the path we’re on especially in the way we understand, treat, and prioritise peoples physical and mental health.

To tackle obesity, we must accept that high incentive food is ‘addictive’ in that it provides an easily accessible, relatively cheap source of significant pleasure, comfort, and relief from stress and distress. As such, treatments must involve helping people to find healthier sources of pleasure that are ‘legal, moral, and non-fattening’! Plenty exist, whether it’s through physical activity and/or social interaction, or through substituting junk food or fast food for healthier food sources that are also pleasurable to consume.

We must also accept that the modern food environment, with its abundance and relentless promotion of high incentive food poses a challenge that can’t be addressed by expecting people to exercise self-control. We need to help people reduce and manage their exposure to this environment without ostracising them. We need to accept that there are many obstacles in the way of people being able to gain long-term control over their weight. As such, we need to accept that people will need guidance, but most of all, they’ll need on-going and unwavering positive support.

If helping people to navigate the obesogenic environment sounds like you, you should consider becoming a Weight Management Coach. You can find out more about this important, rewarding career path here.

References

1. Ministry of Health. (2021). Annual update of key results 2020/2021: New Zealand Health Survey.

2. ANZ-Roy Morgan Consumer Confidence. (2022, February). Darkest before the dawn?

3. Mate, G. (2018). In the realm of hungry ghosts – close encounters with addiction

4. Kenny, P. (2011). Reward mechanisms in obesity: new insights and future directions. Neuron.

5. Kenny, P. (2013, September). Is obesity an addiction? Scientific American

6. Milyavskaya, M. & Inzlicht. M. (2017). What’s so great about self-control? Examining the importance of effortful self-control and temptation in predicting real-life depletion and goal attainment. Social Psychological and Personality Science.

7. Milyavskaya, M., & Inzlicht, M. (2018). Attentional and motivational mechanisms of self-control. In De Ridder, D., Adriaanse, M., & Fujita, K (Eds.), Handbook of self-control in health & well-being

Photo Credit:

Stressed photo by Anh Nguyen on Unsplash