Obesity and the legacy of a simplistic model

Current Models for Obesity

For 50 years we have used the caloric equation as a model to understand and more importantly to attempt to treat obesity.

The equation is linked to the first law of thermodynamics. Simply put, it proposes that if you put more calories into your body than you burn off, the difference will be stored as fat. Therefore, the commonly accepted solution to excess fat storage (obesity) is to; move more and eat less. This is often followed by some inane statement like “you can’t beat the law of thermodynamics”.

Why Calories in Calories out is true, but isn’t effective

The first law of thermodynamics applies to a ‘closed or isolated system’. The law states that energy cannot be destroyed or created, it is constant. The type of energy (chemical, radiant, electrical etc) changes but the amount of energy doesn’t.

From a scientific perspective, food is a cluster of chemicals with bonds between elements. You break the bonds producing energy, and you breathe out carbon dioxide and water. If you take in more energy than you expend, you gain weight. If you expend more energy than you take in, you lose weight. In this way, the caloric equation is true.

The caloric equation is potentially useful in a closed or isolated system with known inputs that are all easily measurable. It’s all very tidy, mechanistic, and logical. However, if the system itself is adaptive then the law is rather ineffective. There are a string of undisclosed assumptions underpinning this model.

One is that energy eaten becomes energy biologically available for use. We know this isn’t true as the amount of food you absorb and what your body does with it varies considerably. Both due to the type of food you eat, your stomach emptying rate and digestive acids, and the bacteria in your colon – to name just a few variables.

There are also large variances in resting metabolic rate between individuals driven by your mitochondrial density and function, the environment, and your genetics. It is estimated that 50% of the variation in any response to energy intake is genetic.

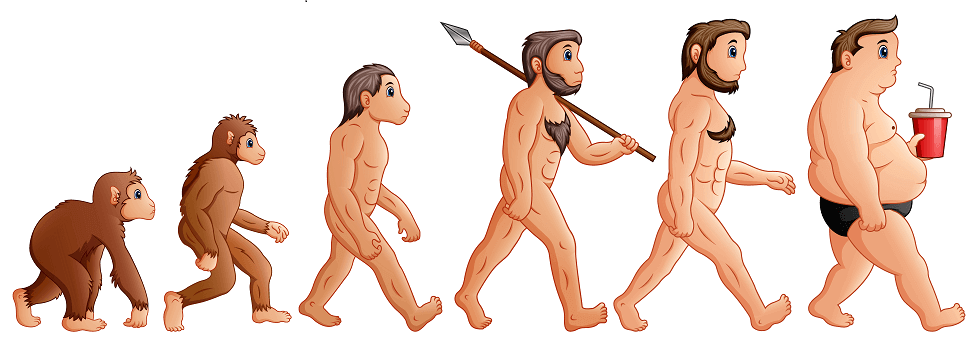

Added to these variances is the challenge that the system itself adapts – this is called ‘metabolic adaptation’. If we overeat, we tend to burn extra calories and if we under eat we tend to decrease our metabolism. Both these evolutionary adaptations have served us well until now.

We can also metabolically prioritise different bodily functions – essentially apportioning limited energy to the biggest immediate priority. When under fed we may maintain energy supply to working muscles but decrease the energy used for immunity, or growth. Again, sensible in a challenging food environment but not the best when there’s a string of fast-food outlets on most main streets-

The caloric equation we have been using is a good chemistry guide but that’s about it. It doesn’t go any way toward explaining why we overconsume or under exercise. The model is not wrong in and of itself, it’s just not of any use for the obesity challenge we are facing.

The caloric equation doesn’t seek to explain why obesity occurs – that is, why does someone overeat for their energy needs or under exercise for their energy intake. It doesn’t define the actual problem causing obesity, so solutions anchored to the simplicity of the model, fail.

Why models don’t always help

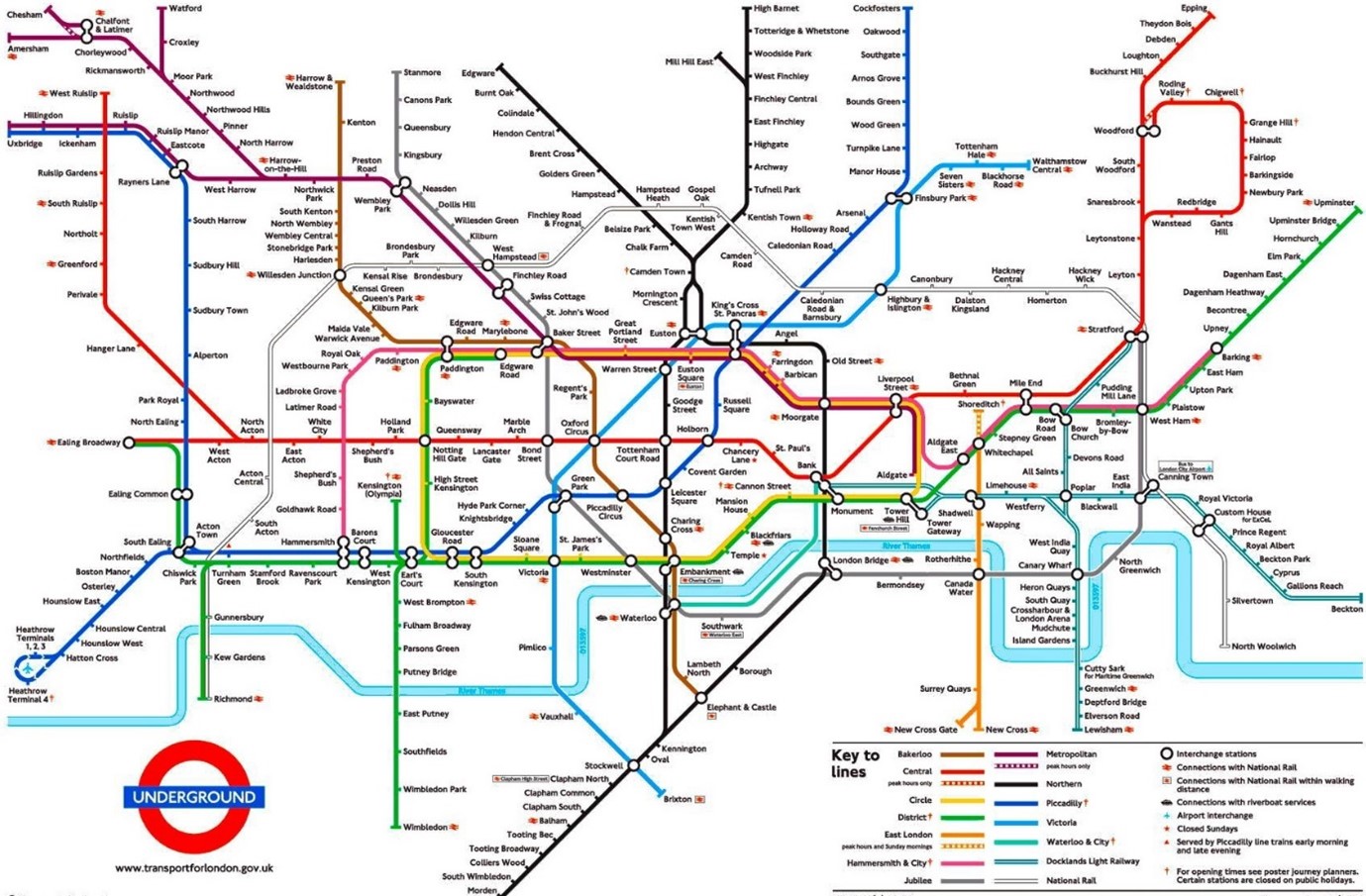

The caloric equation is a model. When you create a model you ‘represent’ something. Like a model of the London underground representing the actual train system. The London underground map is a great model (created by an electrician using the same method you would for modelling an electrical system).

However, the model isn’t to scale (stations are spaced equally in the model but in real life stations can be a few hundred metres away or a mile away), the lines on the model don’t represent the track directions (because as lines were added they had to fit them into the existing model), and the whole of South London has very few tracks (because the majority of trains in that area are above ground).

Interestingly, property has a higher value in areas where there is a station and even higher still where that station appears to be closer to the centre of London – even though it’s not. The stations that appear further out devalue those areas – however the commute time is often less, because the model isn’t reality. The model has overtaken reality and is driving the behaviour (that of purchasing houses).

The important thing to understand here is that with all models you lose information. They are reductionist by their very nature. The more complex the reality is, the more information you lose when using a model.

In describing things with numbers or diagrams you lose the information that really drives the reality. The model itself creates issues because any solutions based on the model won’t address the real problem. Just as you can pay too much for a house in London because you used the underground map as reality, you can create quite strange behaviours by using the caloric equation as a model of obesity.

Here’s a short list of such examples;

- Calorie counting (my favourite example was holding ice in your mouth as water has zero calories, and you need energy to melt the ice. A cold face, as opposed to weight loss, was the only measurable outcome though).

- Being concerned about the calorie value of food, rather than the foods quality, freshness, and nourishment (is 500 calories from donuts really as good for you as 500 calories from fruit and vege?).

- Identifying ‘bad’ and ‘good’ macronutrients based on their caloric value (we must unite against fat, no wait, carbs, no wait protein, no I give up).

- Feeling guilty about eating a high calorie food (so you feel mouth pleasure followed by guilt – which shows an emotional connection to what’s happening rather than any calorie concern).

- Feeling powerful in denying yourself a high calorie food (it is a very righteous act, best witnessed by others and followed by a chocolate bar at home alone).

- Differentiating exercise value based on the number of total calories burnt rather than enjoyment of the activity (I hate rowing, but it burns lots of calories, what can I do?).

- Maximising calorie deficit as a goal for living (when I was six I wanted to be a tennis pro, and then a sport journo – I don’t remember setting any calorie deficit goals).

- Belonging to one tribe or another that beats a simple caloric drum (low fat was the first culprit – no butter, no eggs, no worries – but it didn’t work, so we went low carb – which also won’t work).

- Research that should show the calorie equation works – doesn’t. There’s no evidence that lots of exercise causes lots of weight loss (it generally plateaus), or that a big calorie deficit works (metabolic adaptation occurs), or that equicaloric diets create the same result (generally diets high in real food win out over diets with equal calories from a box).

What now?

The caloric equation has delayed our progress. It has created a dis-association between the value of food in our lives, and the value of activity in our lives. When every action you take can be analysed by the caloric intake or caloric output, the simple joy of living can quickly slip away. As the author Burgess depicts in ‘A Clockwork Orange’ the sweetness of life (the orange) should not be mechanistically controlled (the clockwork).

Those of us who are obese (34.3% of adults with a further 33.7% overweight) live in a world where our shopping carts can be easily judged and if we are out exercising it’s ‘good on him, at least he’s doing something’. We are surrounded by well-meaning ‘experts’ from GPs to nutritionists to personal trainers all harping on about calories in and calories out.

I think it’s time we let go of the model – it doesn’t work, we’re doing more harm than good, and we don’t have the right problem because we lost too much information in the model we adopted. We de-humanised and over-simplified a complex, multi-factorial challenge and in doing so we lost the best chance we had at finding robust solutions.

A phrase I read in my early academic years was ‘the chains of habit are too weak to be felt, until they are too strong to be broken’. Truth be told, this is likely a more accurate description of the obesity dilemma than the caloric equation is. For it’s in habitual behaviours with their environmental triggers, subconscious programming, and biological effects that we may address the challenge of obesity most effectively.