Weight loss diets: Fundamental flaws make weight re-gain inevitable

Our biology promotes weight gain and resists weight loss - a reality that is overlooked by conventional weight-loss diets.

Unless we change our approach to weight loss, obesity rates will continue to rise

You may have heard this often-quoted Einstein saying – The definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over and expecting different results. When it comes to dieting, we’ve been indulging insanity for too long. Sure, the names of the diets change every few years to enable more books and weight-loss programs to be sold, but the central message remains unchanged – to lose weight, you’ll need to abandon your current eating behaviours and do exactly what ‘X’ diet tells you to do.

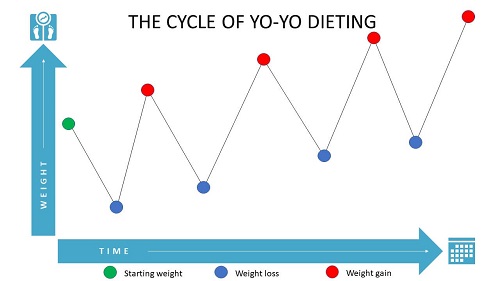

Of course it isn’t that simple, as the longer-term consequences of dieting highlight. Even if clinically significant quantities of weight are lost (≥5% of total bodyweight), this weight tends to be quickly and uniformly regained once the diets end. [1,2]

Now, I’m not accusing those who try to lose weight via dieting of being insane; people who follow diets do so with the best intentions and devote time, effort, and money to following whatever the various diet dictates. Understandably, people believe that diets work because they appear to work (in the short-term) whilst the flaws that make weight regain inevitable are kept well hidden. The net result; people blame themselves for not trying harder, or sticking to the diet for longer.

If these flaws were identified and explained, then the insanity of repeat dieting would become more obvious. Rather than internalising blame for the inevitable regaining of weight, people would seek approaches that address the flaws, and enable them to sustainably control their weight.

The purpose of this article is to help people understand the flaws of weight-loss diets so that healthier, long-term approaches can be pursued.

By the way, if you're interested in helping people to achieve sustainable weight loss, you can find out more about becoming a Weight Management Coach here.

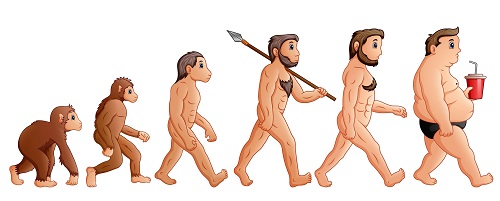

Weight loss diets ignore human evolution – even the ‘Paleo’ diet

Anthropologists have estimated that approximately 99.5% of human history has occurred in environments where food was scarce, not abundant as it is today. Such environments required our ancestors to work extremely hard to gather, hunt, and scavenge enough food just to survive, let alone thrive. Based on the food environments that have dominated our history, which are characterised by scarcity, humans developed several key survival attributes. These include:

- Developing a craving for food that motivates an exhaustive search for it.

- Developing the capacity to overeat so full advantage could be taken of food resources when they were available.

- Developing the capacity to store excess energy as body fat to help survive inevitable periods of food shortage.

- Developing the capacity to be frugal with the use of those body fat stores so they wouldn’t deplete too quickly.

These attributes served us well when food was scarce, they’re not so useful now as ultra-processed foods loaded with added sugar and fat are abundant and readily accessible. The consumption of high-fat and high-sugar foods (HFHS foods) and even the anticipation of their consumption, lights up the reward and pleasure centres of the brain in a similar way that addictive drugs do; enhancing their habit-forming potential.

We salivate at the contemplation of high incentive foods much the same as Pavlov’s dogs were trained to salivate at the ding of a bell.

Our stomachs, made of elastic smooth muscle, stretch almost endlessly to enable large quantities of food to be consumed. Because HFHS foods are ultra-processed and devoid of fibre, their caloric load is far higher than more natural foods. Our well-developed ability to store excess calories as body fat, and be frugal with its use, is exacerbated by the reality that our lives are now largely sedentary.

This reality might not be such a problem if diets were designed to be continued indefinitely – but they’re not. The extreme nature of most diets means that they can only be followed temporarily. The changes in normal behaviour that most diets dictate are simply not sustainable. And when the diet ends, there is no plan or guidance provided for how to deal with the abundance of ultra-processed foods that lie eagerly in wait, ready to help pour the pounds back on.

By the way – simply calling a diet ‘paleo’ doesn’t mean that it replicates the lifestyle and eating behaviours of our hunter-gatherer ancestors. It doesn’t. The only way a diet could do this would be to completely remove all modern ultra-processed foods from the environment, so they’re not available. Then, the environment would need to be shaped so that the natural foods that remained were hard to find, and labour-intensive to access.

The ‘Paleo’ diet is nothing more than the latest marketing spin on a long legacy of high-protein diets.

Evolution has shaped our biology to resist weight loss

The biological adaptations that enable us to crave food, overeat, convert excess into fat reserves and protect those reserves, developed to protect us from weight loss. There’s a good reason for this which is explained through the context of our evolutionary past. Losing weight, whilst living a hunter-gatherer lifestyle where food was scarce, was not only undesirable, it was life-threatening. When you go for long periods of time without being able to access food, survival depends on being able to fuel the body as it searches for food, without fading away too quickly.

Several influential mechanisms are at play here.

Two hormones of particular significance are ghrelin and leptin. These hormones are commonly known as the hunger hormones. Ghrelin is released from the digestive system (the stomach especially) in response to the digestive system having room for food. Ghrelin is positively associated with our feelings of hunger. We often think that our feelings of hunger signal some sort of energy deficit – they don’t. Feeling hungry is simply ghrelin signalling that the digestive system has room for food.

The strength of the hunger signal is dependent on the relative emptiness of the stomach; the emptier it is, the greater the release of ghrelin and the stronger the hunger signal. And the stronger the hunger signal – the greater the drive to find and consume food.

In contrast, leptin, which is released from fat cells, is commonly thought to balance the signal of ghrelin by providing a signal of satiety (or fullness) when our energy reserves are topped up. However, this thinking is flawed and has limited our ability to understand hunger and our current issues with bodyweight.

The increasingly accepted view of leptin is that it sends a signal to the brain about the state of the body’s energy reserves (fat levels). A strong leptin signal indicates sufficient reserves, whilst a weak signal indicates a problem for survival – low energy reserves. In response to low body fat levels (as signalled by low leptin levels), the body reduces its metabolic rate (rate at which it burns energy and depletes energy reserves). It does this by (amongst other things) slowing down or temporarily halting energy demanding functions such as growth and reproduction, which are not immediately essential for survival.

But how does this all relate to flaws in weight-loss diets and the inevitable weight regain that follows?

Weight-loss diets, especially those that produce rapid weight loss, trigger a protective response from ghrelin and leptin. In response to the weight loss, ghrelin levels increase and remain elevated for a significant time after the diet finishes. What this means is that a dieters level of hunger increases as they lose weight, and their hunger levels remain elevated after they finish the diet. Well intentioned dieters are driven to search for more food to satisfy their hunger and regain lost weight.

And in response to diet-induced weight loss, leptin levels decrease and remain depressed for a significant time after the diet finishes. This means that during and after a diet the body slows its metabolic rate to conserve energy. Thus, reducing the ability to burn the extra energy that is consumed to satisfy elevated hunger levels after the diet finishes. The ultimate example of this comes from a popular TV show.

Studies of The Biggest Loser[3][4] found that while contestants often lost huge amounts of weight, most of that weight was regained in the years that followed the show. Some contestants even ended up heavier than when they started. Not only did the contestants metabolic rates drop during the show, but they remained depressed for 6 years after! Season eight’s winner in the US version, Danny Cahill, lost an incredible 239 pounds in just seven months. Despite maintaining a restricted caloric intake and strenuous exercise regime, Cahill had regained over 100 pounds in the post-show period.

In short, diets are flawed because they trigger responses which increase our hunger, drive us to eat more, and reduce the rate at which we burn or utilise that extra energy. Hence, weight regain is biologically programmed into the diet formula.

Weight loss diets ignore basic psychology

At the core of human behaviour lies the principle of reinforcement from the learning model operant conditioning. The model observes that behaviours are initiated and maintained as a function of their consequences. Behaviours that provide immediate and significant positive reinforcement (reward) are more likely to be sustained and/or increase in frequency, than behaviours that do not receive this reinforcement.

At a neurological level, behaviours that are repeated frequently become habitual, meaning that the neural connections that underly the behaviour become strengthened to a point where control over the behaviour is relegated to the deeper, darker, unconscious regions of the brain. This is important as it free’s up neural processing power for higher level cognitive tasks such as preparing for an impending exam, work meeting, or dinner date.

HFHS foods are manufactured specifically to exploit this basic psychology and its underlying neurology. They are optimised to deliver the maximal possible reinforcement, immediately upon consumption. This makes their consumption likely to be repeated to the point where consumption becomes habitual and occurs without much or any conscious thought. The function of food marketing, via media or product placement in stores, is simply to trigger the habitual consumption of these foods. And there’s a heck of a lot of triggering going on across all media platforms, shops, and even schools.

I bet you could name at least five, if not 10 popular food (or drink) brands that you’ve seen marketed today. It’s unlikely that any of them would be what we consider to be ‘healthy’.

You can think of habitual behaviours as the code that runs every computer programme – you can’t change the programme without modifying the underlying code. This is the same for our habitual eating (and drinking) behaviours. You can’t change these behaviours without developing an understanding of the neural programming underneath – what’s initiating or triggering the behaviour, and what’s reinforcing it.

Weight-loss diets ignore, or simply pretend that peoples hardwired habits miraculously disappear – they don’t. In testimony to the power of the conscious brain, people can suppress these habits, but only temporarily. Whilst on a diet, people work very hard to ‘stick to it’ – they concentrate their conscious efforts because for a few short weeks, losing weight can be ‘top of mind’.

Life however has a way of shifting our priorities – kids, family, work, relationships, mortgages, rent all have the capacity to take over and demand the attention of our conscious brain. When this happens, as it always does, those hardwired eating habits kick in again. Often, this can occur with something as apparently innocent as the wafting aroma of KFC as you drive past on outlet.

Behaviours can only be changed by understanding and modifying the underlying architecture that supports and runs the behaviour.

There is hope though – sustainable weight loss can be achieved

Despite the fundamental flaws in diet-oriented approaches, there is hope. Sustainable weight loss can be achieved but it requires a fundamental shift in thinking and methodology. Rather than focus on foods and macronutrient ratios whilst assuming that people will be able to change their behaviours to accommodate a diet, the focus needs to become oriented on behaviour modification.

A behaviour modification approach doesn’t require people to make large, generic, and unsustainable changes to their existing behaviour(s) and assume those changes will stick. Rather, skilled Weight Management Coaches help people to gain an understanding of their current behaviours as they relate to bodyweight, so that these behaviours can be modified to become healthier and conducive to achieving sustainable weight loss.

The approach used is inherently personal as everybody’s behaviours are influenced by different factors. For example, it may involve helping a person to understand that their mid-afternoon muffin and coke is driven by a need to escape a boring office job and interact with fellow workers, albeit for 15 minutes (the reward).

Understanding this could lead to the person deciding that the muffin and coke could be replaced with an OJ and apple. As long as the OJ and apple enable the person to gain the reward of interaction with their peers and temporarily escape their office boredom. A new afternoon behaviour is likely to be sustained, with significantly fewer calories consumed, because the trigger and reward from the behaviour is properly understood.

Now this example is reasonably simplistic, there are a range of additional factors that will need to be considered and addressed to help bed this change in. It’s likely that the coke and muffin will receive more prominent display and price incentives than the apple and OJ (in most food outlets anyway). And the ‘treat and comfort’ nature of the coke and a muffin may have more appeal to the peer group of the person involved – and we generally like to fit in with our peer group rather than isolate ourselves from them with our behaviours. Such factors need to be considered and addressed, which Weight Management Coaches are equipped to do.

While a behaviour modification approach is not without its challenges, it has significant advantages over diet-oriented approaches. The focus on building healthier, sustainable behaviours minimises the yo-yo effect on bodyweight that is typical of diets where a large behaviour is adopted for a short period of time only.

By individualising the approach, Weight Management Coaches can help people to understand and account for the specific factors that influence and drive their behaviours, and their behaviours alone. By working with people as opposed to dictating change, Weight Management Coaches equip their clients with the knowledge and skills required to modify a range of unhealthy behaviours.

It’s time to stop indulging the insanity of diet-oriented approaches to weight loss and embrace a healthier, sustainable, and empowering alternative.

References

1. Ge et al. (2020). Comparison of dietary macronutrient patterns of 14 popular named dietary programmes for weight and cardiovascular risk factor reduction in adults: systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomised trials. BMJ.

2. Franz et al. (2007). Weight-loss outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of weight-loss clinical trials with a minimum 1-year follow up. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics.

3. Fothergill et al. (2016). Persistent metabolic adaptation 6 years after “the biggest loser” competition. Obesity.

4. Kolata (2016, May 2). After the biggest loser, their bodies fought to regain weight. The New York Times.

Photo credits:

Ronald hiding photo by Erik Mclean on Unsplash